Localisation as a buffer against disruption

Fostering anchor institutions and community-ownership can make cities more resilient in tumultuous times

This is the second article of a series on the case for economic localisation, intended as a way to strengthen cities’ economic resilience to financial, commercial, and geopolitical disruption.Whether or not Donald Trump will once again row back on his latest tariff threats, the disruptive effects of his erratic trade strategy are already showing. Businesses are taking note and cities, where the majority of the world’s businesses and people are based, should do so too.

Large cities cannot protect themselves from such disruptions by becoming entirely insular—but they can re-orient part of their economy to establish and support anchor institutions, which act as stabilisers (more on this later). From the establishment of the earliest urban settlements, the success of cities as manufacturing, service, and cultural centres was made possible by the imports of goods from outside the city. At first, this was mostly the lands surrounding the city, but this has now expanded into a more globalised trade network of dependence for both essential and luxury goods. In a recent paper, urban geographer Matt Thompson asked whether a “regionally self-sufficient, internally-diverse, finely-mixed, circular, foundational and, above all, democratic urban economies [will] ever be materialised at the global scale?”. This is a more ambitious vision than that of economic localisation we are exploring in this series, but it is a question worth asking as we explore how cities are to meet their residents’ needs while taking climate action and looking after the environment. (Another paper, just published in the first edition of the Routledge Handbook of Degrowth, touches on the same challenge for cities from—you guess it—a degrowth perspective).

Grounded cities or competitive ones?

In a 2017 paper, Dutch geographer Ewald Engelen and his co-authors drew a distinction between ‘grounded’ and ‘competitive’ cities that is helpful to understand how cities see themselves when they set their policies. They argued that grounded cities maintained a relationship with their wider metropolitan areas and were more focused on activities that had a “stabilising effect” on the local economy: meeting housing, food, utilities, and mobility needs. Competitive cities are instead focused on attracting dynamic and “accelerating” sectors: technology, financial markets, property development. By this definition, competitive cities are prone to economic booms and busts.

No city is entirely “grounded“ or “competitive”, but most city policies’ objectives can be mapped on a spectrum between the two definitions—a good question to ask is: does this policy target residents’ daily needs or aim to increase the city’s profile and competitiveness?

Localising a city’s economy is about making sure that the ‘grounding’ sectors of the economy are resilient to the inevitable disruptions that will affect the competitive ones. This is not dissimilar from ensuring that a building has strong foundations before attempting to build a roof terrace. Challenges such as the energy transition, the housing crisis, and geopolitical disruptions should inspire city leaders to work with local businesses and institutions to reinforce the foundations of the urban economy.

An increasingly popular example: Community Wealth Building

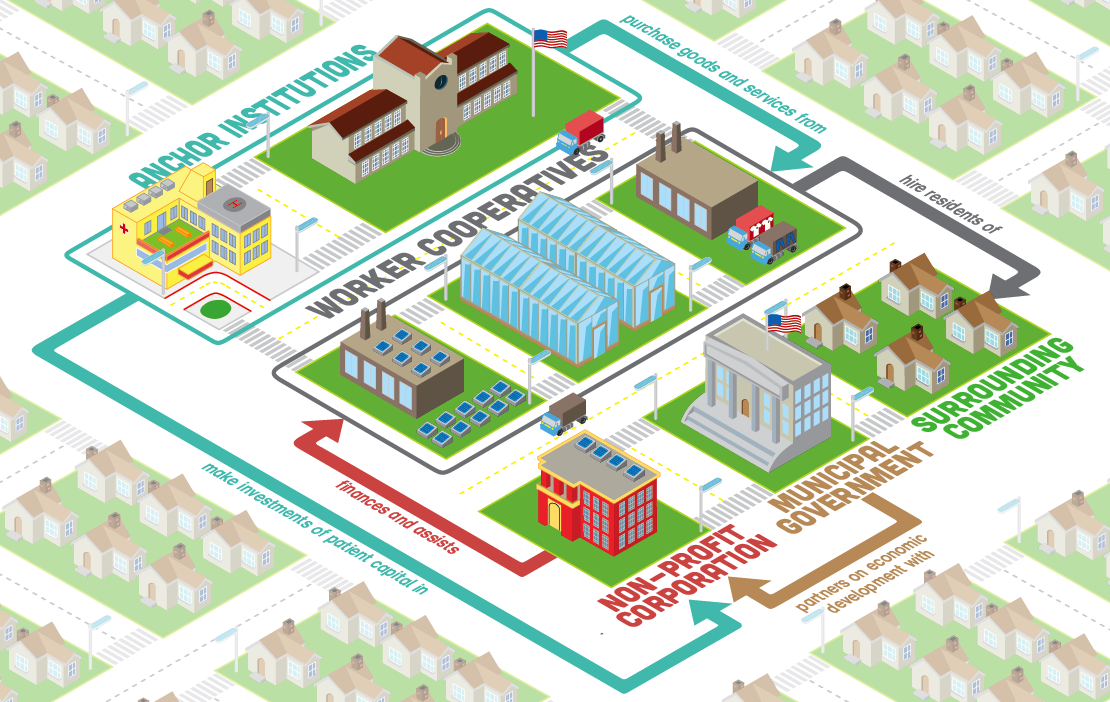

Community wealth building is an economic development approach aligned with the “grounded city” perspective. Its most popular applications (at least among policymakers) are the Cleveland Model in the USA and the Preston model in the UK. In its simplest form, community wealth building aims to harness the spending power of local anchor institutions to support the creation of collective economic ownership of key parts of the local economy:

Production: via worker-owned co-operatives and employee-owned businesses;

Land use: via community land trusts, housing co-operatives and social housing;

Finance: via community banks and credit unions.

The benefits of the community wealth building approach are not limited to local economic empowerment. Alongside a faster than expected increase in median wages, evidence from the implementation of the programme in Preston, UK shows life satisfaction increased and the prescription of antidepressants decreased. A testament that community wealth building can have a material impact on improving health as well as economic resilience.

Using anchor institutions as economic buffers

It is not inherently better or worse for a city economy to be highly or lightly reliant on anchor institutions. But, in line with the thinking behind the grounded and competitive cities outlined earlier, anchor institutions can act as a buffer against economic disruptions, such as the structural decline in manufacturing employment or the sudden shocks caused by trade and financial crises. A 2024 brief from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia looked at whether increasing reliance on anchor institutions in the healthcare and higher education sectors has been good or bad for regional economies and found that, because they are less likely to move or close, universities and hospitals can have a stabilizing effect on urban economies.

This is why many are following the example of Cleveland and Preston. In London, the Borough of Camden set up a community wealth fund focused not only on creating value for residents but also distributing it. If the approach were expanded to a larger share of Camden’s budget (c. £300 million / US$640 million per year), its impact could be significant.

A solution that works at smaller scales too: community-ownership

The benefits of localisation policies are not exclusive to large, stable anchor institutions such as hospitals and universities. For relatively smaller scale projects, community-ownership can be an effective vehicle to ensure wealth generated locally stays local. For example, community-owned wind energy projects in Scotland generate up to 100x more local wealth than privately owned ones, despite accounting for just a small fraction of the overall electricity generation capacity.

Examples such as these are a good way to imagine the role of localisation policies: while it is unlikely that community-energy can be rolled out at the necessary pace and scale to be the the only solution needed for the energy transition, it provides a great case study on how localising a small proportion of a city’s economy can bring outsized gains to local communities. Similarly, it’s not necessary for the whole economy to be “grounded” or “localised”. Large wealth generation and resilience benefits can emerge even if a relatively small proportion of the economy is re-directed towards purpose-driven, locally-focused businesses and co-operatives.

🔜 What’s next in this series

In the upcoming newsletters we will talk about the climate case for (and in some cases against) economic localisation; the required shift in Government thinking (from fixing market failures to preventing them); the political appeal and the perils of economic localisation; and much more.

Journal Special Issue on Urban Riskscapes

The latest issue of our Journal of City Climate Policy and Economy, published in collaboration with the University of Toronto Press, asks how cities, their institutions and residents can respond to increasing levels of climate risk.

With the right funding, cities can better protect people from devastating climate impacts like heat, flooding, and storms. But local governments often miss out on the money they need, even in wealthier cities.

Find all the entire issue here, with all articles available as open access.

Going Steady, an upcoming mini-series on Herman Daly from the Cities 1.5 podcast

This August, join host for a special podcast series from Cities 1.5, dedicated to Herman Daly, an economist who transformed how we think about growth. Featuring never heard before interviews with Daly himself, Going Steady tells a story you won’t want to miss.

You can listen to the trailer here. Subscribe to Cities 1.5 and join us for the first episode on 19 August.

📚 What we are reading

: I recently read La ficción del ahorro by Carmen M. Cáceres. I love books set across a short span of time that capture a mood. This one is set in 2001 Argentina. Using a bundle of cash as the point of departure, the novella follows the young daughter of a middle-class family and through her eyes questions the supposed virtue in saving money and resting our hopes on a point that is forever in the future set against the backdrop of a country and economy in perpetual crisis. And even if you don’t like the plot, just read it for the prose!

‘Si ahorrar es vivir en otro tiempo, desahorrar es alojarse en un presente radical. Esa ha sido siempre la verdadera alquimia de la clase media argentina: su voluptuosa capacidad para transmutar la energía no en prosperidad, sino en permanencia.’

: I’m currently reading Second-Hand Time by Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich. A collection of interviews to USSR citizens describing the experience of living through the fall of their cultural system and their disenchantment at the unkept promises of Russian freedom and democracy.

David Miller: In the Garden of Beasts - Erik Larsen’s historically accurate novel about the increasing horror of the newly appointed ambassador of the United States of America to Germany in 1933. I have only just started, but the book is riveting. History might not repeat. But it does rhyme.