Making cities more resilient by “localising” their economies?

Can the capacity to be more self-reliant help cities navigate uncertain times?

This is the first of a series on the case for economic localisation, intended as a way to strengthen cities’ economic resilience to financial, commercial, and geopolitical disruption.The USA’s trade tariffs announcement on 2 April 2025 caused near universal panic in financial markets and political circles. This widespread alarm was not solely the consequence of the bizarre way in which these had been calculated, but the fact that many of the goods impacted had no immediate alternative markets or, for US buyers, no immediate substitutes: with global supply chains being so intertwined, financial pain for businesses and consumers seemed inevitable.

In financial markets, that initial shock has now faded—though this is largely because of the majority of tariffs being temporarily suspended. However, it is now hard to unsee the potential disruption to which the wider economy is vulnerable and it would be unwise not to consider how cities can protect themselves from such negative shocks.

Learning from past vulnerabilities

The disruption feared when the USA announced its tariffs can be compared to the 2022 global energy crisis, sparked by a reliance on Russian fossil gas for which European countries had no immediate alternatives, but which had become unacceptable in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Europe’s response to that energy crisis was diversification and localisation: European countries rushed to diversify their suppliers and reduced gas consumption by 20% via demand management, sped up efforts to improve its energy efficiency, and increased domestic renewable energy generation, ultimately reducing their reliance on fossil fuel imports and dramatically bringing down energy prices.

This series of newsletters will look at how economic localisation can make cities more resilient to global financial, commercial, and geopolitical shocks—and why localisation is consistent with ambitious climate policy.

What is economic localisation?

For our purposes, a desirable economic localisation policy is about cities being connected to—not reliant on—others, at least for a core share of goods and services that are necessary to protect residents from the volatility of markets. This is a difficult balance to find—not just in the current interconnected economic system, but from a historic perspective too. The economies of many civilisations relied heavily on trade millennia before the emergence of capitalism. For example, the loss of trade relationships in the Mediterranean basin is among the causes that archaeologist Eric H. Cline identified as the drivers of the Late Bronze Age collapse (12th century B.C.), alongside—ironically enough—a changing climate.

Interestingly, we lack a shared understanding of what economic localisation is and what it is for. Some authors argue it is about giving communities power to decide on issues that affect them (see Micheal H Shuman’s Going Local), others take a more radical position in suggesting localisation is about limiting trade and reversing globalization (see Colin Hines’ Localization: a global manifesto).

What is certain is that the latest USA’s tariffs do not appear to be a form of economic localisation. Depending on whom one asks, the tariffs are aimed at reducing the country’s trade deficit or are simply a way to force countries into negotiating with the USA on issues that are not necessarily trade-related, whereas an economic localisation strategy would be designed and implemented to improve the economic resilience of its residents.

What options do cities have?

On one extreme, there is autarky, or self-reliance. While it reduces vulnerability to foreign disruptions or conflicts, the isolation that inherently accompanies autarky has the unintended consequence of amplifying the effects of any domestic crisis by making it difficult to receive support at times of need. For this reason, no country or city in the world is pursuing full autarky, which remains a policy usually implemented out of need (see fascist Italy or, in part, present-day North Korea) rather than utility.

On the other, total openness and reliance on international markets is also a gamble that rarely pays off: while large corporations can survive in highly volatile markets, this is more challenging for smaller businesses and individual households, which is why the use of subsidies for goods considered essential (like bread or fossil fuels) is widespread and hard to wind down both technically and politically.

Between the two extremes, there is the present situation: urban economies that are globally interconnected. Currently, cities are more focused on reaping the benefits of the global economy than protecting themselves from its potential shocks. This works well in unproblematic times, but leaves them vulnerable during crises.

Cities seeking to increase their self-reliance will face the challenges familiar to those who usually lobby for local resilience-building measures, let’s call it a value-for-money test. Is the additional reliability and stability worth the additional cost? This may sound abstract economic thinking, but it is—in essence—the thinking behind any privatisation of public services (which trades off local control and institutional knowledge for savings promised by advocates for outsourcing).

An effective economic localisation policy would see cities increase their self-sufficiency in the production of things that are necessary for people’s wellbeing and have no immediate substitutes. Not everyone’s “necessities” will be the same, so this definition may seem arbitrary, but so was the definition of “key workers” during the pandemic—this is why cities should be leading this effort, which cannot be left at the mercy of the private sector.

An obvious example of economic localisation policy would be to increase the production of renewable energy to reduce reliance on volatile fossil fuel prices, gas pipelines, and oil tankers. Andrew Sissons, Deputy Director at Nesta, a UK-based think tank, recently wrote an excellent piece on the case for a little more autarky in the energy sector. His main point, which greatly influenced my thinking for this series, is that the ideal situation would be to enjoy the benefits of trade and exchange while retaining the possibility of becoming more self-reliant when necessary. With its visible power stations and international interconnectors, the electricity sector makes this process easy to grasp, but the same principles could be applied across more diverse urban economies globally.

🔜 What’s next in this series

In the upcoming newsletters we will talk about the climate case for economic localisation; the required shift in Government thinking (from fixing market failures to preventing them); Community Wealth Building and other localisation policies for cities; the role of businesses and residents in increasing urban resilience; the political appeal and the perils of economic localisation; and much more.

🎧 The latest episodes of the Cities 1.5 podcast

In last week’s episode, our host David Miller spoke to Henrique Goes (Clean Construction Manager at C40 Cities) about how clean construction is helping the planet and creating good green jobs and to Vivek Parekh (lead on the oil and gas industry lobbying work stream at climate think tank Influence Map) about the fossil fuel industry’s tactics to stop building electrification.

And in this week’s episode, for our Season Finale, David talks with Katie Walsh (Head of Climate Finance for Cities, States, and Regions at global non-profit CDP) and Andrea Learned (climate influence catalyst and strategist) about the importance of data and information for climate action and what other ingredients are key to effective communications about global heating.

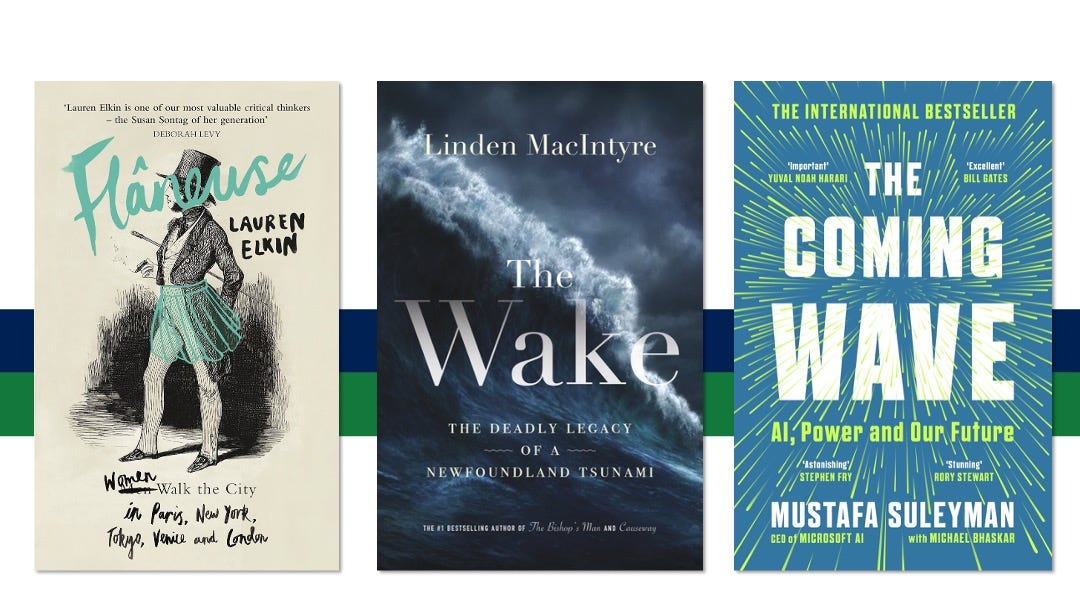

📚 What we are reading

: I recently finished Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London by Lauren Elkin. Exploring the liberating and political dimensions of women walking, it made me feel at times more purposeful and at times more exhausted on my own urban walks.

: The Wake by Linden MacIntyre. An extraordinary true story about the deadly legacy of a tsunami in Newfoundland in 1929, and the legacy it left in economic dislocation in small outport fishing communities, who turned to mining fluorspar in newly opened mines owned by capitalists from New York City. Significant health issues for miners ensued, yet the jobs mattered critically to the community. A true account of the challenges of localization vs globalization, The Wave is well worth reading to see what really can happen after a natural disaster—particularly when the profits of far away owners are the first priority.

: I’ve just finished The Coming Wave by Mustafa Suleyman. The book is a long-winded way to say Artificial Intelligence will create a swathe of existential risks, but we shouldn't stop its development (unsurprisingly, as the author is a founder of AI businesses and current senior executive at Microsoft). Interestingly, the solutions he puts forward include empowering governments with in-house skills and protecting people with a strong financial safety net. The book also predicts a marked increase of leisure time as a consequence of the AI rollout, a bold claim given that leisure time is also the one prediction John Maynard Keynes got wrong, and that evidence is so far the opposite—AI is creating more work as it cannot be trusted to be correct.

Nice series, I look forward to reading the upcoming posts!

You might be interested in the work of Matt Thompson:

https://academic.oup.com/cjres/article/17/3/535/7710625?login=false

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382447656_Economic_development_from_growth_to_degrowth