We need to talk about urban climate migration

Migration can be a powerful climate adaptation solution, but national governments' lack of vision puts cities on the front line, adding to their existing challenges.

There are times when the long-term future looks less uncertain than the immediate one. Investors refer to this phenomenon as yield-curve inversion—when short-term bonds offer higher interest rates than long-term ones, a sign of trouble ahead—but readers of this newsletter in the Spring of 2025 may refer to it as “the present”.

So, looking beyond the immediate future, this newsletter focuses on an often overlooked, long-term adaptation solution for the climate crisis: migration—and C40’s latest research on this. Failure by national governments to act puts even more pressure on cities, as they deal with the present and future millions of displaced people in search for a safer home.

An old idea for a new problem

We know that, even in the most optimistic scenario, we will need to adapt to a changed climate and that the world’s adaptation efforts will be complex and expensive ($215 billion per year by the end of the decade, according to UNEP). There is no silver bullet for climate adaptation, mostly because the challenges posed by a changed climate are varied and unpredictable. Climate-related disasters are already a significant cause of internal displacement and migration (largely rural-to-urban). Adding international migration into our portfolio of climate adaptation actions makes sense.

Adaptation via migration means letting people move to safer places if they want to: a simple idea, but not an easy one. Gaia Vince’s 2022 Nomad Century - How to Survive The Climate Upheaval offers an informed provocation on the topic.

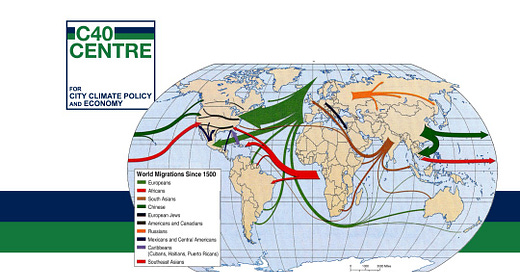

In her book, Vince refers to migration as humanity’s oldest adaptation strategy: limits to the movement of people across the world are a relatively modern phenomenon that creates an arbitrary and cruel bureaucratic barrier to human adaptation and therefore to human wellbeing.

Vince suggests that countries that will be spared by the worst impacts of the climate crisis—predominantly those in the Global North—should see climate migrants as an asset to rejuvenate their economies and build new cities to house them. This is in stark contrast with today’s reality: the majority of displaced people are internal (within their country of origin) and when they do move, they do so within and between Global South countries, largely due to the financial, cultural, and bureaucratic hurdles of moving further away. To address this, Vince argues that the international migration process could be fair and safe if overseen by a global agency with real powers and the introduction of a global citizenship along the lines of Nansen passports. However visionary, the idea was not particularly popular when the book was published in 2022 and is even less so in 2025.

The moral case for establishing safe migration pathways for people affected by the climate crisis is clear: humans have always migrated; the Global North should help those affected by its historic emissions (this is at the core of the loss and damage discourse); it would prevent great and unnecessary suffering. But these reasons alone are not enough to overcome the barriers to implementing such a radical proposal.

The barriers to establishing safe migration pathways

The biggest obstacle is public perception and political viability. Migration is frequently among voters’ main concerns—not because they care about it, but because they want less of it (a fear that is stoked by many politicians, predominantly on the right and far-right). And while there are instances in which migrants may be welcomed, such as when fleeing conflicts, a 2023 study published in Climatic Change showed that “reading about climate-induced immigration resulted in more negative attitudes toward immigrants”.

The economic case for migration exists, but it is relatively small. Migrants make a small but positive fiscal contribution to their host countries (they pay more in taxes than they cost in services), they generate innovation (in the U.S. immigrants accounted for 30% of all patents in strategic industries), and start successful businesses (46% of companies in the 2024 Fortune 500 list were founded by immigrants or their children). However, their contribution is not sufficient to make them welcome: a meta-analysis from the Immigration Policy Lab showed that people’s opinions are not swayed by economic concerns (i.e. “will migrants drive down wages?”) but by perceived cultural differences. It is hard to see a way around this in the present political environment.

Another huge challenge is providing safe settlement—that is, appropriate housing and services that are accessible and well-integrated with host economies. Most progressive countries and cities, who tend to be the ones whose residents are most open to immigration, have a poor track record of building at the pace required to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Unaffordable housing in most global cities and widespread infrastructure bottlenecks that prevent prompt renewable energy rollouts are the visible consequences of such inertia. Difficult to imagine these hurdles would be overcome to achieve such a politically charged objective.

Where this leaves cities: preparing for unmanaged displacement

The fact that creating safe migration pathways is not politically viable will not deter people from trying to leave places that will become unsafe. Effectively, cities will be left dealing with the expected unmanaged displacement of a large portion of humanity.

Cities are the best places for migrants to go. They are where it is easier to build physical and social infrastructure and, ultimately, where the best education and employment opportunities can be found. But there are risks too: without the implementation of extensive adaptation measures, cities will be just as vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis as the rural areas many people will be leaving.

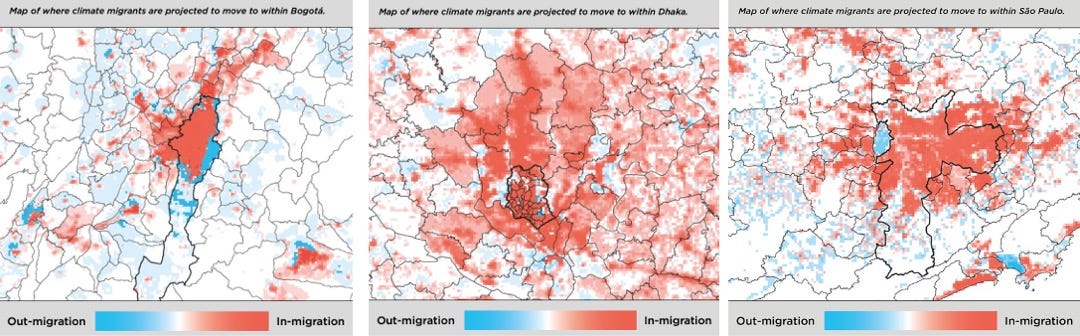

Recently, C40 Cities published a report showing that by 2050 ten urban areas in the Global South (Accra, Amman, Bogotá, Curitiba, Dhaka, Freetown, Karachi, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, São Paulo) could expect up to 8 million migrants due to the climate crisis alone.

The scale of the challenge for all cities is huge, particularly given the pre-existing pressure affecting local governments, but there are clear actions that can be taken now to improve cities’ adaptation chances:

Rapidly reduce emissions: decisive mitigation actions to prevent worst case climate scenarios and reduce future cost of adaptation.

Give cities resources: ensure city governments have access to funding and financing to plan for caring for larger populations in and around their administrative boundaries;

Empower planning departments: they will need access to data and resources to ensure cities’ housing and infrastructure can withstand upcoming climate impacts while remaining vibrant, inclusive and liveable.

Ensure migrants are included: cities should prepare to welcome people that are displaced and national governments remove administrative barriers for migrants to access services and work opportunities.

Managing new residents in cities risks exacerbating existing challenges, such as overcrowding or overstretched local services, but the good news is that cities have proven themselves equal to these challenges before.

Few other inventions have been as successful as cities at improving the life chances of the human lot. Throughout history, people have sought refuge in urban areas and turned hamlets into cities and then into metropolises. Climate breakdown is the crisis of our time, but the way in which people adapt to it does not need to be—including through migration, if properly managed and planned for. From this perspective, Vince is right: the expected scale of migration in the 21st century is a great opportunity.

🎧 The latest episodes of the Cities 1.5 podcast

In last week's episode, and his guests Kate Johnson, Regional Director for North America, and Amy Turner, Director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative at the Sabin Center, Columbia University discuss the future of the Inflation Reduction Act, the challenges cities, mayors and US residents are facing, and how they are fighting back against the attempted rollback of urban climate action.

In this week’s episode, we explore how different cities are acting as urban laboratories to test out alternative economic ideas and models to neoliberal ones with guests Angelos Varvarousis, Research Fellow at Autonomous University of Barcelona, and Takehiko Nagumo, Director of the Smart City Institute Japan.

📚 What we’re reading

: I recently read Denominazione di Origine Inventata (“made-up designation of origin”) by Alberto Grandi. A provocative book about how more of the revered Italian cuisine is owed to Italo-American emigrants than the romanticised tales of century-old recipes suggest. For anyone looking to craft a convincing story, take note!

: I’m looking forward to reading Luca Misculin’s Mare Aperto (“Open Sea”) which promises to touch on both my interest in human migration and my fascination for the stories and cultures of the Mediterranean Sea. Whether it will be able to replace Your Baby Week by Week on my bedside table, that’s another matter…

Carbon does not drive climate change, it's the sun and the earth's orbital variations. Your entire thesis is a delusion based on shoddy science and garbage-in-garbage-out computer models. Your fixed false belief system is as primitive as the medieval witch-hunters who burnt women at the stake thinking it would stop crop failures.