Fear. If you grew up in Germany in the 90s chances are this feeling played a role in your everyday life. It has been a fixture in the German pre-schooler pedagogy since at least the early nineteenth century, when the Grimm Brothers sought to increase the ‘didactic value’ of fairy tales such as Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast by replacing the originals’ raunchier elements with violence and punishment. Around this time of the year, the figure of Knecht Ruprecht, St Nicholas’ frightening companion, scares children into submission at the threat of the birch if they misbehaved during the year gone by.

Fear is not only a feature of my childhood but of my work on climate communications today: by some counts, up to 98% of environmental news stories are “negative”. Implicit in this number is the conventional wisdom among many communicators that increasing people's fear of climate change are necessary precursors for action and behavior change.

And in some instances, generating fear does inspire action. However, it only does so when the fear seems personal and a solution feels concrete, doable, and meaningful. The COVID-19 pandemic is a good example. COVID-19 posed a threat to people’s personal health and safety and many governments offered a doable solution: stay at home.

But I knew it from Christmases past, as in-fighting with my siblings was an unmovable feature in spite of Knecht Ruprecht, and I was reminded by a recent talk with Dr Kris de Meyer from the UCL Climate Action Unit on the neuroscience on climate change: fear is not an effective tool to lastingly guide people’s actions.

More diffuse threats such as global heating require a myriad of solutions at different societal levels, these are hard to be perceived as concrete, doable, and meaningful at the individual level. A concrete and doable solution for global heating is to put solar panels on one’s house, though it is not meaningful in the sense that, once the panels are up on my roof, I can stop worrying about climate change.

What is more, for such “diffuse threats”, instilling fear can trigger a whole range of reactions, including hopelessness, disengagement, active rejection, and denial. Yes, individuals are sometimes driven into action by fear but, as a strategy to drive action across society, fear leads to fragmentation and polarisation.

Scaring people into action won’t do it—what then?

With fear banned from the climate comms toolbox, what else can we use to garner support for climate action? Rather than pulling on other emotional strings, the single most effective tool is getting people to do something first. Agency, caring, and awareness will follow. This strategy is grounded in the basic functioning of our brains as studied in social psychology dating back to the 1950s. Action is the precursor to strong beliefs and not vice versa. This is due to positive feedback mechanisms: The moment one decides to take an action, a burst of activity in the brain, a “neurological pat on the back”, rewards us for the decision we have just made. Positive responses received from people around us can further reinforce this loop.

A Little Less Apprehension A Little More Action Please

If taking action is key to driving climate beliefs, how can we inspire people to do so? Dr Kris de Meyer and his team conducted extensive research on this question, culminating in this formula: through place-based stories of transformation driven by individuals and communities. This is good news for C40 and its cities and in particular for the C40 Knowledge Hub! If you haven’t yet come across this resource, the C40 Knowledge Hub identifies tried-and-tested approaches, practical guidance, and insights and experience from cities already working on climate issues, and shares them in formats designed to be accessible and digestible. Some of their stories include how Amsterdam is implementing a circular economy, how Bogota established Clean Air Zones or how Denmark built an inter-municipal network of cycle superhighways.

Come to think of it, the primacy of concrete action over fear-mongering was already clear all those Christmases ago. The actor impersonating St Nicholas on our street would readily relinquish a coveted gift upon listening to a credible account of good actions I had performed rather than the horror story of the pranks my little brother had pulled.

To many good climate deeds in the new year!

🎧 The final episode of our Cities 1.5 podcast season 4 is now live.

Why is it so crucial for cities to adapt to protect against the health impacts of the climate crisis? And when the worst happens, how can we rebuild, resiliently? In the final episode of the season, host David Miller speaks with Professor Stella Hartinger Peña, world-leading Peruvian Epidemiologist and Environmental Health Specialist, about her work on the Lancet report on climate change and health, how the climate crisis is impacting on frontline Andean communities and why cities need focus on adaptation.

We also hear from @mayorcantrell who shares how she has been supporting New Orleans to rebuild and create a healthier and more resilient urban home for all residents.

Listen here.

📚 What we’re reading

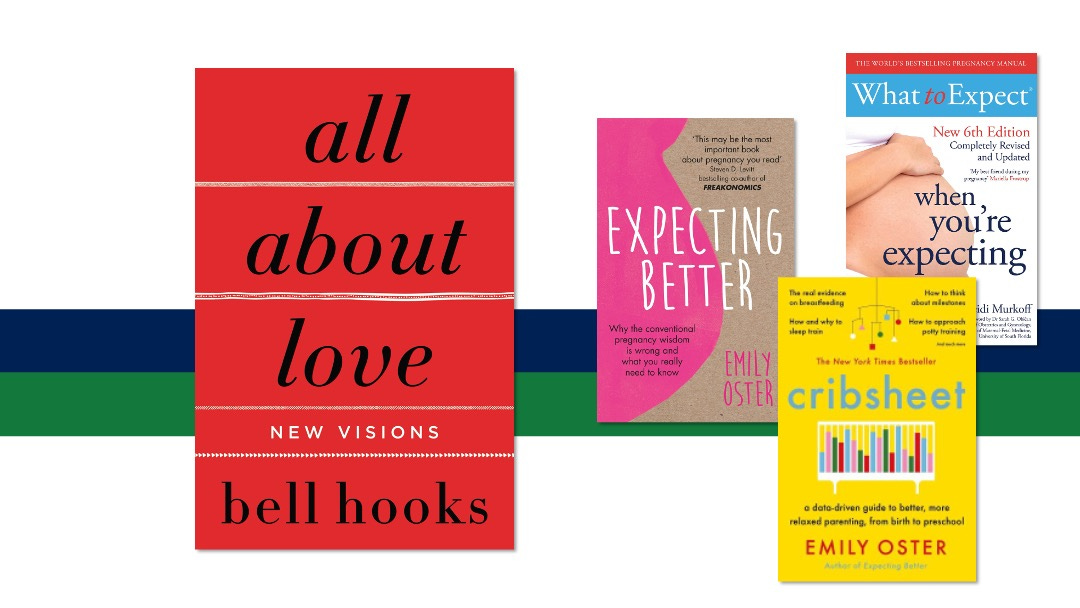

: All about Love by bell hooks. A good read on the role of love for individuals, communities and society. Useful ahead of any seasonal engagement with family members as well as climate work.

: My reading-for-pleasure time is greatly diminished as more of my time has been devoted to pregnancy/parenting books (if you have any actually good recommendations, please send them my way—the whole genre appears to be a perversely repetitive spin on self-help books). Two things that stuck with me lately are a piece on how—because of climate change—haikus are becoming increasingly detached from the time of the year they historically described and an article on urbanisation and light in which one of the paragraphs nonchalantly begins with the line ”Consider that more than a fifth of all mammal species are bats.”