A new worrying estimate of the economic damages of climate change

A new paper suggests the impacts of climate change may be six times worse than previously thought, but it also offers hope that governments will act unilaterally to accelerate mitigation efforts.

A new working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that the economic damages from climate change are six times larger than previously thought. If the results of the paper are confirmed, they leave no excuse for inaction by government and business leaders—and should change the (unhurried) way they have gone about their climate mitigation efforts to date.

The findings are no reason to indulge in climate doomerism (for a healthy dose of which may I recommend Jonathan Franzen’s New Yorker essay What if we stopped pretending). Instead, the working paper offers food for thought both in terms of how the authors reached their results and of the policy implications that follow the new knowledge about larger-than-expected damage to the world economy.

An innovative approach to reach shocking conclusions

Previous studies (from as far back as 1992 to as recently as 2023) have underestimated the impacts of climate change on the economy, at least according to the new working paper authors, Adrien Bilal of Harvard University and Diego Känzig of Northwestern University. These studies suggested that a 1°C increase in the world’s temperature would reduce the size of the world economy by 1-3%. Instead, Bilal and Känzig find that a 1°C increase in the world’s temperature lowers world GDP by up to 12%. The difference is explained by the fact that previous studies focused on country-level, local temperature shocks, whereas the authors focus on global temperature shocks, which they maintain have a much more pronounced impact on economic activity than local temperature.

The most shocking result of the working paper’s innovative approach is the 31% present value welfare loss from a moderate warming scenario. (Throughout the working paper, the size of the economy as measured by GDP and the term ‘welfare’ are used as near-synonyms, though readers of this newsletter will know the difference between them.)

This is not the only paper published in the past few weeks that makes the economic case for rapid climate mitigation even more powerful. Last month, the results of another paper in Nature showed that the projected damages of the climate crisis “already outweigh the mitigation costs required to limit global warming to 2°C”. That is to say, as a society, we have no economic excuse not to ramp up our climate mitigation efforts today.

The results of the working paper by Bilal and Känzig also imply that the social cost of carbon amounts to US $1,056 per tonne of carbon dioxide. (The social cost of carbon is a measure of the costs and benefits of emitting an additional tonne of carbon dioxide.) This is much higher than the range of US $120-$340 estimated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, meaning that it makes more sense to do more now to prevent further emissions.

What does this mean for real world policy?

The most interesting implication is that the working paper’s results make unilateral decarbonisation an optimal strategy for large economies (the paper specifically mentions the United States of America), as many decarbonisation interventions cost less than the newly estimated cost of carbon. It is a remarkable finding, as this was not the case under the estimates provided by previous studies. Historically, the lack of a clear economic case for unilateral action put pressure on achieving unanimous international collaboration on emission reduction plans. This resulted in frequent finger-pointing towards the rising emissions of developing economies, for example. We can hope that, armed with this new perspective, the larger economies start moving towards unilateral decarbonisation at a faster pace than that of global climate diplomacy.

The magnitude of the working paper’s results is scary, but its findings are also empowering. We now have a better idea of the steep costs of inaction, but we also know that unilateral action to tackle the climate crisis makes sense not just morally, but economically too.

📚 What I’m reading

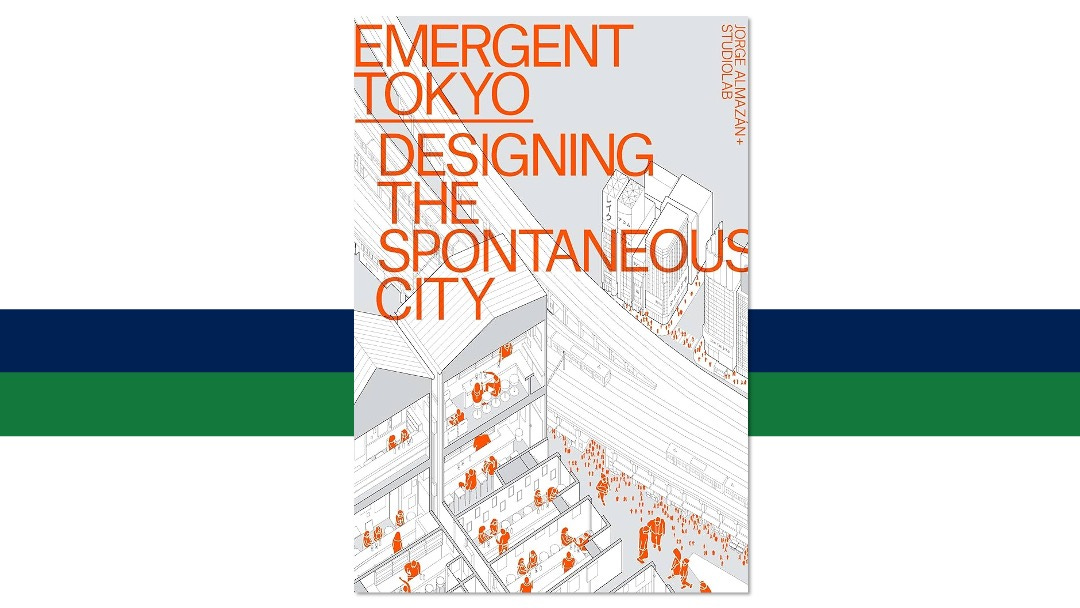

I’m taking great pleasure in Emergent Tokyo, a visually striking guide of the historical urban planning quirks that make Tokyo such a great place.